Career Profile: What is Engine Turning? with Watchmaker Seth Kennedy

Engine turning is an increasingly scarce mechanised engraving technique, which involves the use of a turning engine to cut intricate, repetitive patterns onto a metal surface. At the peak of its popularity, engine turning was used to decorate compact mirrors, boxes, hairbrushes and watch cases and dials, before its widespread use began to wane, and many machines were scrapped.

In modern times, the continued survival of this historic technique is dependent on the small group of craftspeople that remain proficient in it. Among these is London-based professional Antiquarian Horologist Seth Kennedy, who acquired the skill through a QEST (Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust) Scholarship, and who intends to one day pass the skill to another fellow craftsperson.

What does an Engine Turner do, and how would you describe the job of an Engine Turner?

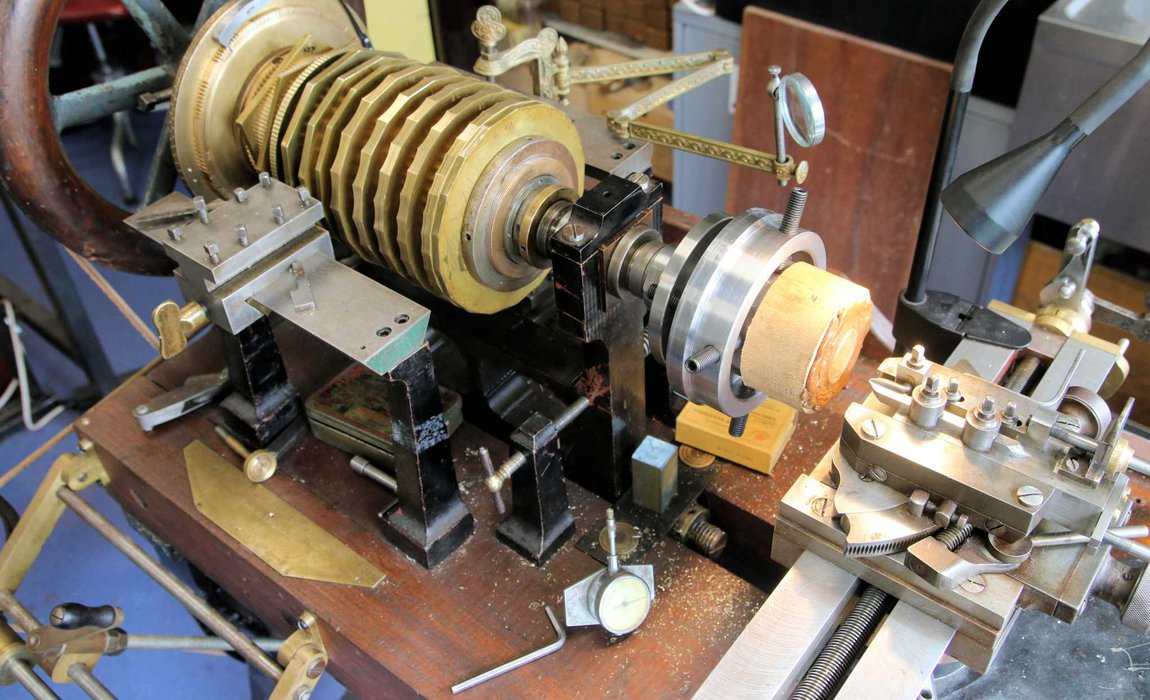

Engine turning is a very old mechanised engraving process which started to become popular in the mid 18th century. Historically, a lot of decorative items were engine turned, and as a horologist, I first discovered the technique as it was used a great deal on watch cases, from the late 18th century to the start of the 20th century. It's a purely decorative process, it doesn't add anything to the mechanism of an object. An engine turner uses a machine such as a rose engine for engraving, cutting patterns on the surface of the metal. Different machines produce different effects, like straight or curved lines, or rotary or linear.

To what extent is engine turning used in your job?

Not a massive amount, you will struggle to find a craftsperson in the UK whose profession is just engine turning, for most people it’s just a part of their job. I know just one person who’s primarily involved in engine turning as a subcontractor, Steven Keen, but I think he is the last of his kind. Steven is training me through my QEST scholarship. For me, when I make watch cases, not very many of those will end up being engine turned, but I do use engine turning on other things, for example I've just used it on metal caps for scrolls, for a client. So there are ways of keeping the machine busy and exercising that skill, but it does make up a small proportion of my work.

Why would you choose to use engine turning over a more common form of engraving?

Primarily because of its evenness, for want of a better word. It creates precise geometric patterns, but in a very regular manner. So you don't have any of the flaws that might occur during hand engraving - if you want to call them flaws - and you can’t really recreate, through hand engraving, an engine turned pattern. The whole point of engine turning is that it creates a very even pattern, and with the light reflecting off that pattern, your eye picks up even the slightest error in it, which is why when you're turning something, you have to really concentrate and get it right. You can't go back and start again. So it's a fairly intensive process, but the main reason for using the technique is that it produces a different technique that is really eye-catching, especially when it's put under clear enamel, which is very common.

Why is it so uncommon?

It's come in and out of fashion. Its last spike in popularity was in the middle of the 20th century, when all sorts of objects like hair brushes, toiletry boxes and compact mirrors became very popular. Then as a style, this went out of fashion, and I think the skill almost died out as a result. A lot of machines ended up being scrapped, so now there’s a limit on the number of machines out there, and on how many people have the skill.

Personally, I think, with hand crafts gaining more interest in modern times, there's a real opportunity for engine turning to be revived. To some extent, it will never reach the highs that it has in the past because there's just not enough people to do it, but I think for anyone wanting to use it as a finish on decorative objects, there's an opportunity to grab these machines, which are now basically antiques.

There is a chap in America who makes brand new machines. Engine turning is an offshoot of ornamental turning, a similar mechanised geometric technique that is applied to soft materials like wood. This gentleman makes engines primarily for wood, but you can also use them for metal. Other than those engines, your only option is to buy an old machine.

Examples of different engine turned patterns © Seth Kennedy 2023

Examples of different engine turned patterns © Seth Kennedy 2023

So what first sparked your interest in engine turning?

I discovered it through the watch business. I handled pocket watches, dials and cases which the technique had been used on. When I started case making about seven years ago, I wanted to get into engine turning so that I had that skill.

How did you learn this skill?

I received a scholarship from QEST, who support craftspeople to learn new skills to improve their repertoire. They paid for one-to-one tuition with the specialist engine turner, Steven Keen, that I mentioned earlier. I’ve been very lucky to get that training, but I'm still learning the skill. It requires an awful lot of practice as well, and that's on my own time.

What does an average day look like if you're working on a project that involves engine turning?

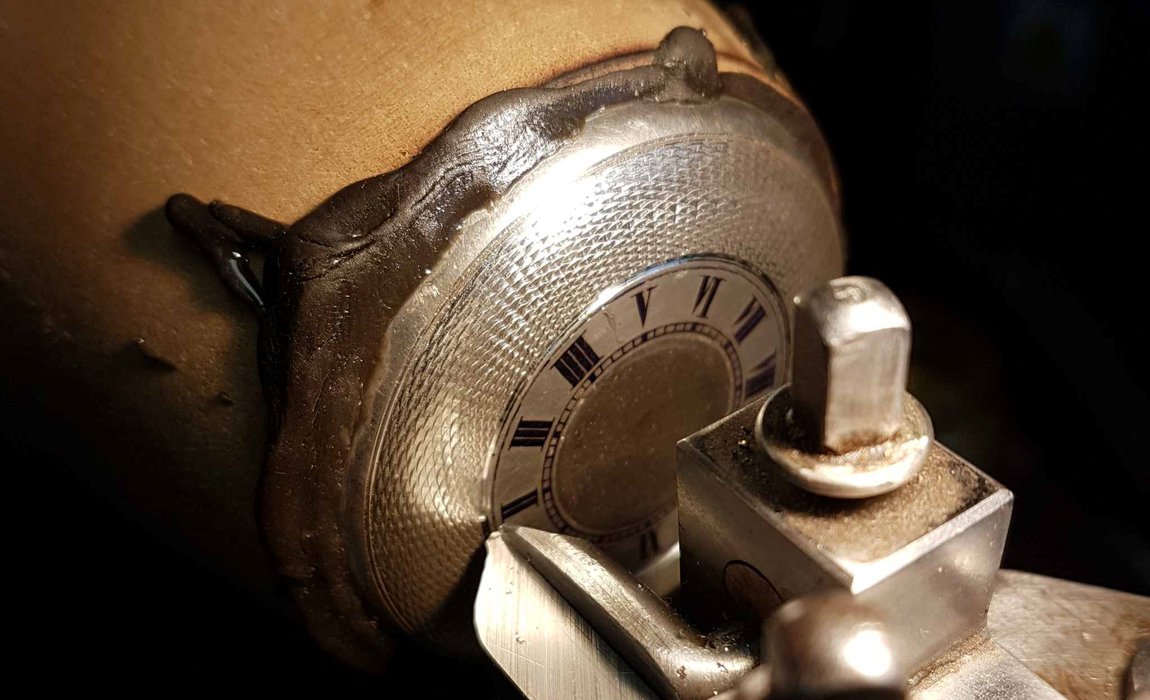

An average day for me involves a mixture of repairing existing watch cases and making new ones. When something requiring engine turning comes along, sometimes I'll have to devise the method of holding it on the machine so that it’s not going to move. I use fairly traditional methods - mounters wax or pitch, which is the same wax that hand engravers use. Depending on the shape of the object, I might need a piece of wood to turn on the lathe, and then use the pitch to hold it in place.

Then I’ll be focusing on tool sharpening, making sure that all the tools are ready to use, and sometimes working out what pattern I want to cut by doing a trial run on a blank brass disc or something like that, to ensure that the settings are in the right ballpark for when I start working on the actual piece. Then it’s just a matter of getting in the right frame of mind, getting in the zone to sit there and work through the process.

What's most challenging about engine turning?

It's particularly difficult to engine turn domed objects. Flat objects, once you've been doing it for a little while, are not that tricky. I’ve been restoring a watch case and re-cutting the pattern on it because it's worn so badly, and that's very hard. Besides that, just trying to keep the concentration level and not get distracted is hard - you must make sure that you don’t mess it up halfway through, because there's no going back. So it depends on the object, and generally it takes a few hours.

What's your favourite thing about engine turning?

Knowing that I'm keeping a craft alive that is at severe risk, that comes with a sense of responsibility., I feel like I need to pass the skill on myself at some point. There’s also the joy of doing something that's so unusual and so rare. When you end up with a finished object that people can then look at and enjoy, that’s obviously a nice thing, too - there’s a sense of achievement.

Is there a project involving engine turning that you're most proud of?

I was pretty pleased with a project that involved recutting an old watch case - that worked out well. You can really only do that once, as once it's worn away, it really depends on the thickness of the metal as to whether you can recut it again. That's the sort of thing I'm most pleased with, when you can look at the before and after pictures, and see how much a piece has changed.

Do you think it's important to keep this craft alive?

It's a sense of history and a sense of where we come from that it's difficult to reproduce. That work that you get off a rose engine isn’t something that can be achieved by any other means, so it does give a unique and unique finish to an object. That’s something you want to lose. I've done quite a bit of research fairly recently on the engine turners in the 19th century, and I’ve come across all these characters and stories, and you just think - well I'm just an extension of them.

Do you plan on teaching someone else?

I hope so, I think that’s an important part of being involved in a craft.