Boasting is out, Beauty is in | The Brooch Unpinned

Our exhibition, 'The Brooch Unpinned' celebrates the art of the brooch in Britain from 1961 to the present. We tell the story through the jewels themselves, which have been chosen to show a maker at their most characteristic - and we have added a few surprises for good measure.

Brooches may only be one element within the Goldsmiths Company’s extraordinary Collection of Modern Jewellery, but these highly wearable accessories give us a unique insight into the story of contemporary design and making in precious metals. That inspired us to explain something of who we are and what we do as a Company through the lens of this miniature artform.

My article from Apollo Magazine looks at the thinking behind The Brooch Unpinned and its debt to an earlier Goldsmiths’ Company exhibition, 'The International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery', which took place at the Hall in 1961. It was a display that showed what post-war jewellery could be; not only by intermingling antique and contemporary jewels but also by setting pieces from the great houses alongside experimental pieces cast from models by leading sculptors and artists of the day. With these commissions, the Company began to collect studio art jewellery in precious metals.

It is in a sense the wearer who makes a brooch. The exhibition was sparked by the capacity of a single brooch – Lady Hale’s diamanté spider – to trigger a global conversation. During the UK’s Brexit negotiations in 2019, Baroness Hale sported a dramatic glittering spider to announce a key judgement of the Supreme Court. She later claimed that she had not intended to convey a particular message, but her audience on social media seems to have thought otherwise, hailing her as 'The Spider Woman'.

The relationship between brooches and the body, and with textiles, underlines the role of micro-engineering in making a brooch work. Weight, construction, balance and fixing are intrinsic to successful functional design if a brooch is to sit well on the body. As all jewellers know, a look at the back as well as the front of a brooch will reveal how well it works as wearable art. This is why we have incorporated graphics in the exhibition to show brooches back to front: to illustrate their microengineering and to take people closer to individual sponsor’s marks and inscriptions which place each brooch within a maker’s biography. The result is an informal kind of collective biography, told through the jewels themselves.

Some of our research and thinking for the exhibition centred on the relationship between women and brooches, as both makers and wearers. So we have the remarkable Dr Helen W.Drutt English, patron, advocate and art donor, in a blog about the brooches in her life and their meaning for her. Jewellery expert, Dr Joanna Hardy, presents one of her favourites in her own collection - a brooch by Gimel.

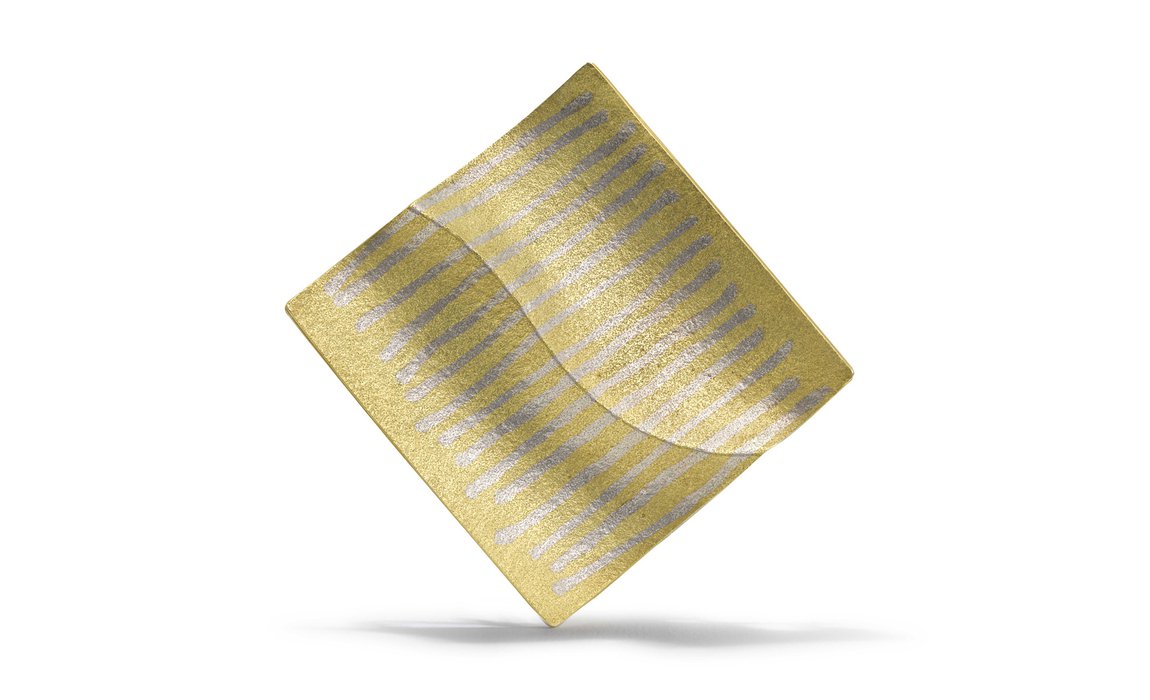

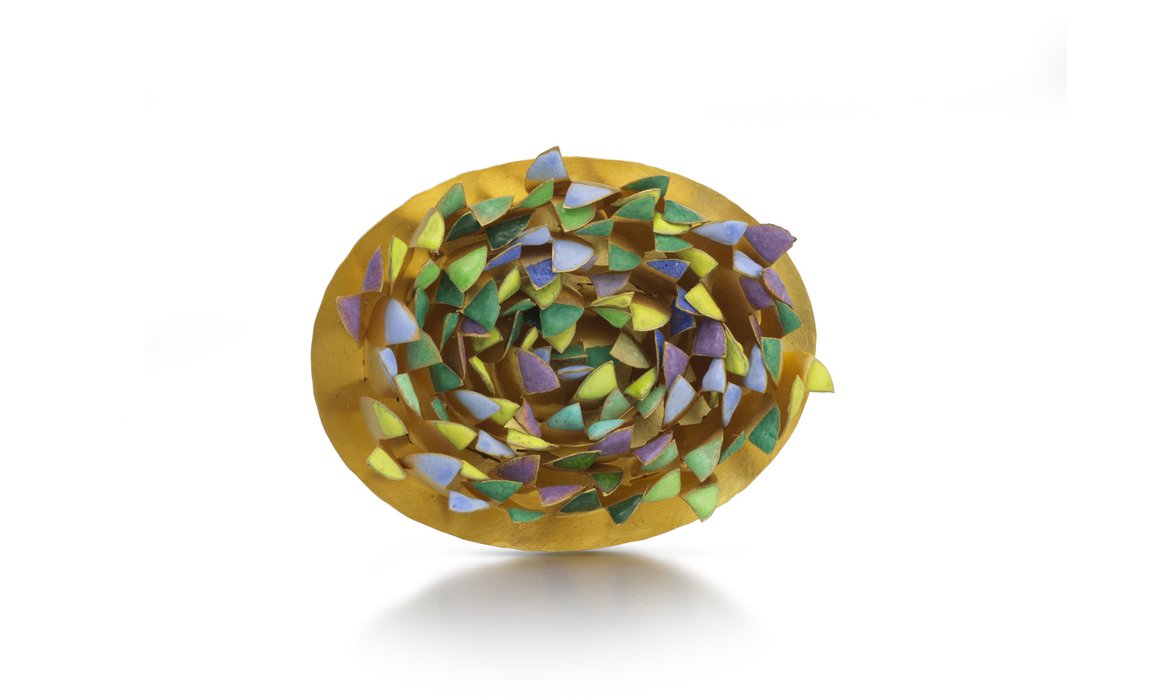

Women as makers is a rich field of research: conversations with some of our leading makers opened up our understanding of their work. In the exhibition we have one of Charlotte De Syllas’s earliest works in what has become her famous signature technique, that of gem carving. We consider some of the techniques she uses to carve semi-precious stones in her superb sculptural pieces in this article. Daphne Krinos revealed the story behind the making of her fine openwork brooch as documents for her Greek heritage and the inspiration of the London cityscape. A recent acquisition of a beautiful and colourful brooch, 'Primavera' by Jacqueline Ryan led to a closer examination of her unique style of enamelling on gold. Jacqueline Mina talked to us about the origins of her fusion inlay technique which involves the upcycling of otherwise rejected materials—something which often involves giving new life to things which would otherwise be thrown away. Jacqueline also explained the inspiration she draws from ancient jewellery as a contemporary goldsmith.

Men and brooches - a developing interest in contemporary fashion and making - is explored in a series of blogs, starting with how one curator, James Robinson of the Victoria and Albert Museum, fell in love with a brooch crafted from layers of paper by Nan Nan Liu. The simplest brooch can be the starting point of a relationship with a maker and his work, as in the case of John Moore. The earliest brooch experiments of John Donald as he played with relatively inexpensive materials to create new sculptural forms of expression is the subject of another piece. 'A Voyage around Kevin Coates' looks at the story of one jewel, 'Serlio Doorcase' from 1983, and its genesis as an exercise in Renaissance proportion and the Golden Section.

What it all shows is the reinvention of the brooch as an art form, as makers increasingly have increasingly begun to consider its volume, surface texture and materiality in sculptural terms. It is a story which continues today in showing some of our latest commissions for the Company Collection. We hope the exhibition will inspire the next generation of makers and a greater appreciation of the art of the brooch as `experiments in form’.

Image Credits: Jacqueline Mina, Brooch, 2004. Photography by Clarissa Bruce. Ute Decker, ‘Rolling Waves in Moonlight’ brooch, 2017. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection. Photography by Richard Valencia. Jacqueline Ryan, ‘Primavera’ (Spring) brooch, 2018. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection. Photography by Clarissa Bruce. Kevin Coates, ‘Serlio Doorcase’ brooch, 1983. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection. Photography by Clarissa Bruce.