Modelling: An Introduction to Making Master Patterns

Being able to create a high-quality master pattern which provides excellent reproductions will help you when trying to cast or batch produce your work. This article is part of a series on different approaches to modelling and what you need to be aware of.

As we move into a world where anyone can reproduce three-dimensional pattern work and sculpting in CAD/CAM it is, perhaps, useful to have an overview of how modelling has been practised in the recent past and reassess its relevance to us in the here and now. It probably still has a use for those who cannot afford the high set up cost of the relevant programme and 3-D printer.

No one knows this better than Mark Gartrell FIPG who, having been modelling and sculpting a range of high-quality items for over 50 years, has established himself one of the UK's most adaptable workshops with the ability to design, model, cast, silvermith, chase and finish pieces in-house. And it is Mark's ability to be able to analyse each design and successfully select the most relevant processes to use which have allowed Mark to produce a wide range of work.

In this article Mark explains his approach to producing a master pattern including his approach to selecting materials and the problems that various materials can pose.

“All this is intended to illustrate that choosing the right modelling medium and further enhancing its handling performance is most important and must be constantly born in mind.”

Master pattern production

When I produce master patterns, I require strength in my chosen medium so that I can model to very fine tolerances in order to accurately follow the working drawing I am provided with. All the waxes and materials described here are available to purchase in the UK from well-known trade suppliers.

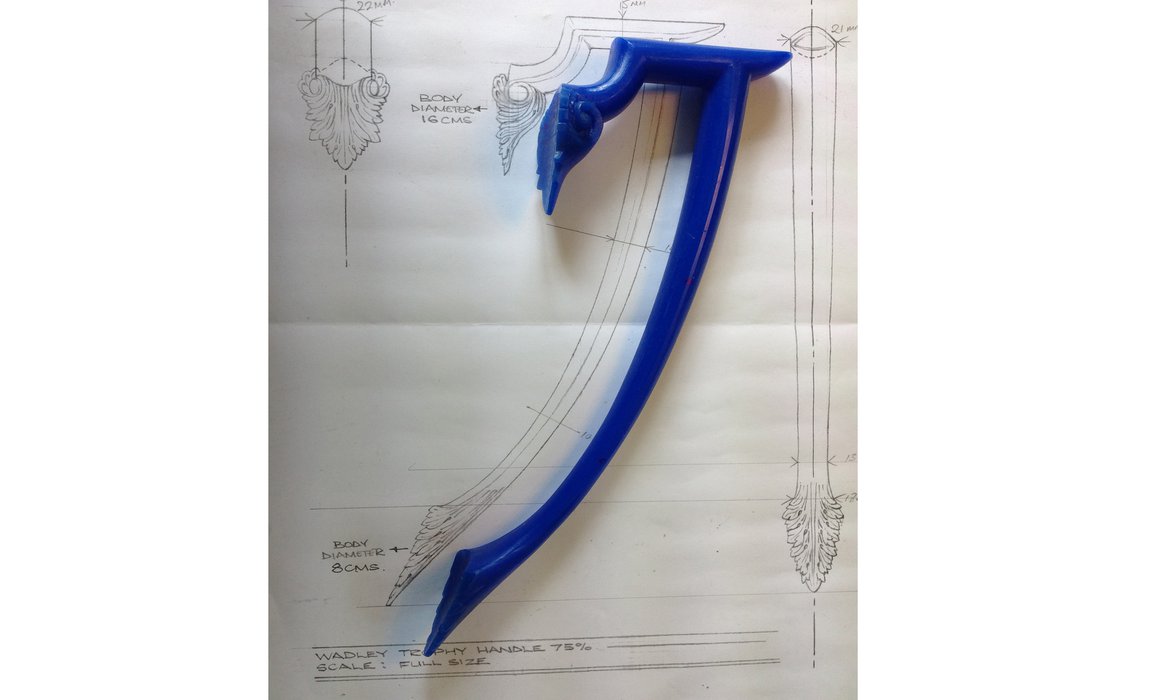

For the purposes of this article I will be discussing the production of a master pattern for a sporting trophy handle. For this specific handle, I use machinable hard blue carving wax, which I can saw and file quickly to shape. It is ideal, furthermore, as it is not affected by normal workshop temperatures so doesn't sag or distort. Having created the basic shape the handle can be handheld so that fine detailing like scrolls or acanthus can be easily applied in a softer medium like a Plasticine or a casting slush wax. The Plasticine can be modelled on cold, whilst slush wax will need to be applied with a hot wax needle and carved/scraped back with modelling spatulas.

Sporting trophy handle modelled in wax according to a working drawing

Sporting trophy handle modelled in wax according to a working drawing

How do I use modelling materials of varying hardness?

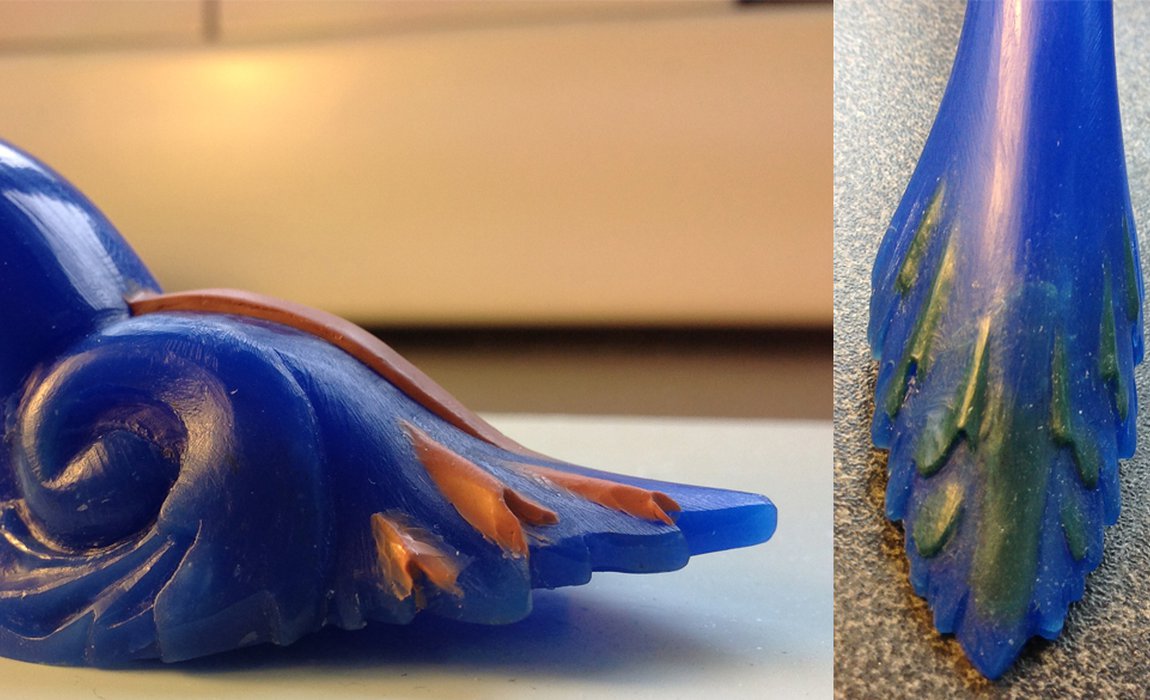

Sometimes I use both media so that I can build up my modelling in layers with the hardest at the base supporting successively softer layers. I liken it to using grades of solder - starting with enamelling solder, proceeding to hard solder, then medium solder and on to easy solder. Each layer of modelling is softer than the lower stratum, thus the lower layer is firmer and therefore doesn't distort. If everything was modelled in one medium the job would be so much more difficult. When we are not struggling against an inappropriate medium, we will achieve a much finer end result. Because of this some of my models will be produced in quite a variety of different coloured media and even look faintly ridiculous. This is irrelevant as the silicone rubber moulds all media equally and the end result is what concerns us.

Detail on the sporting trophy handle created using different modelling materials

Detail on the sporting trophy handle created using different modelling materials

How can I make models look natural or life-like?

In another recent project to produce a silver sculpture to celebrate the bicentenary of the Battle of Waterloo, research showed that the Duke of Wellington wore a cloak on the day of the battle. A cloak hangs free from the body and must look like natural material hanging down. This, of course, is much more difficult than modelling jacket or trousers onto a body which gives a solid shape to apply wax to. To overcome this problem, I stock a dental wax which is sold in rectangular sheet form, 1.5mm in thickness, and can be purchased from dental suppliers or good art shops and it is called Astynax.

Having the proper medium for this task I produced a full-sized template from polythene sheet and draped it over the figure of the Duke until satisfied that it looked right. I then welded sheets of Astynax together until it was the size of the polythene cloak and cut the sheet to the template. I was then able to heat the pink dental wax with a hair dryer and, when soft, to form the cloak between my fingers. To have modelled from a medium like Plasticine would have been impossible and the end result would have looked dreadful.

The Duke of Wellington’s cloak modelled to look realistic and natural

The Duke of Wellington’s cloak modelled to look realistic and natural

How do different material hardnesses affect modelling?

The portrait head of the Duke I modelled in slush wax allowed me to hand hold the head and work up very close using an Optivisor. To try to handhold Plasticine would be a disaster as it would quickly overheat and become soft. The slush wax proved very helpful as the head was so small that it had to be modelled completely with spatulas as my fingers, although my best modelling tools, are just too big at this kind of scale. Even hands shaking at small scale modelling must be taken into account as a soft Plasticine medium is all too easy to ruin when the hand shakes.

The main modelling medium I use is actually not Plasticine, as whenever I buy it from different art shops; I find its hardness varies which is for me unacceptable. I buy a French medium, Plastiline, which comes in a variety of hardnesses. Its quality is uniform and non-variable and the little extra in purchase price is well worth the ease of use it gives and probably speed of use repays such outlay. When using Plastiline I warm it in a slow cook electric stockpot. As this has an adjustable thermostat, I set it to a temperature suitable to the job in hand. A sculptor friend talks of the small pieces of wax that you instinctively pick up to apply to your model as thought sized pieces. When these pieces are all the same temperature work proceeds so much quicker.

On occasions when I have large areas to sculpt, I will adjust the stockpot temperature upwards and rapidly lay up large amounts of Plastiline with a plastic palette knife. I, of course, return to 'thought sized pieces' to impart the critical detail later on. My old friend the hair dryer is also of great use to warm discrete areas of a model or to rapidly warm models that have gone cold overnight and lumps that need to be quickly moved. Cheating at every level is enthusiastically encouraged in my school of modelling.

To familiarise oneself with the effect of heat on materials when modelling I would suggest a simple experiment with two lumps of Plasticine - take two lumps off a warm radiator and slap them together. They of course meld, just as wrought iron hammer-welds together when red hot. Now put one lump into a cold fridge and the other back on the radiator and a little later slap them together again. One deforms the other of course. So, we can think in terms of modifying material performance with temperature.

We can also think in terms of altering the intrinsic nature of materials, to aid forming, by alloying. We can vary the hardness and mouldability of waxes by mixing hard with soft, or even, in the case of Plasticine, introduce filler powders to increase resistance. All this is intended to illustrate that choosing the right modelling medium and further enhancing its handling performance is most important and must be constantly born in mind.

Conclusion and further infomation

And don't presume that you have to do it all yourself. In increasing your understanding of some of the materials, processes and techniques that Mark has encountered throughout his career, you are better able to make the right production decisions for yourself and, where required, find the right craftsperson for the job. Good luck!

There are many reputable sources of information relating to the jewellery, silversmithing and allied industries. Whether you are trying to find information on technical skills, processes, materials, makers or inspiration some resources relating to modelling can be found below:

The Goldsmiths’ Company Library relates specifically to gold and silversmithing, jewellery, assaying and hallmarking, precious metals, and the City of London and its guilds. The Library includes 8,000+ books and 15,000+ images, magazines, periodicals and journals, technical guides, films, special research collections, design drawings produced during the early and mid-twentieth century by British or UK-based craftspeople and subject files on a wide range of industry related topics. The Library is also responsible for the Company’s archives, which date back to the 14th century.

Modelling related articles include: