From Brief to Brooch: Trainees Experience the Realities of Designing a New Consort Badge for The Dyers’ Company

There’s something uniquely powerful about learning through doing - especially when working with a real-world client and the outcome has true impact. This year’s collaboration with The Dyers’ Company, a 550-year City of London Livery Company promoting the dyeing industry and craft, offered just that: a live design brief that challenged our Jewellery Foundation Programme trainees at the Goldsmiths’ Centre to create a gender-neutral Consort Badge for the Prime Warden’s partner, an emblem blending symbolism, history, and contemporary design.

This was more than a design challenge; it exemplified the true value of project-based learning. From initial sketch to final prototypes, students navigated a complete professional design workflow. They explored the rich legacy of The Dyers’ Company, drawing inspiration from centuries-old traditions and the architectural details of Dyers’ Hall itself. Along the way, they built skills in critical thinking, presentation, CAD modelling, and material experimentation - all while learning how to respond to a client’s evolving needs.

Now, the journey has come full circle with the creation of a delicate swan-shaped brooch formally presented to The Dyers’ Company. To mark the occasion, we sat down with the winning student, Laurie Callister-Davies, runner-up Amy Wiedmer, the Goldsmiths’ Centre’s Programme Manager for Vocational Training, Lili Capelle, and the tutors Jasmin Karger and Steve Jinks, who guided the project from concept to completion. Together with past Prime Warden of The Dyer’s Company, Jamie Cawley, they reflect in their own words on the creative process, the challenges they overcame, and what it means to contribute to a piece of contemporary heritage.

From Concept to Commission: Choosing The Dyers’ Company Live Brief

Jamie: My wife, Diana, was the Consort for 2024 and was taken on a tour of the Goldsmiths’ Centre. She was very impressed by the work going on and wanted to help, if possible, with the trainees on the Jewellery Foundation Programme. The Dyers had been looking for a Consort of the Prime Warden’s badge and/or brooch for some time, since the last one was lost. The piece needed to clearly identify the Consort and be suitable for anyone to wear, across all sorts of occasions. Together with Lili, we thought it would make an ideal subject for a first-year project

From there, Diana wrote a brief, and the students came to see Dyers’ Hall to get a feel for the Company and its iconography. The students were asked to come up with at least three concepts, exploring both traditional and contemporary takes on the Dyers’ visual identity - using elements like the crest and the swan, and experimenting with enamel, metal, or colour combinations. The brief really pushed them to balance creativity with practicality, making sure the design was elegant, versatile, and durable.

Lili: We were looking for a project that would really challenge students – something that would get them thinking about real-world constraints, heritage symbolism, and professional design practice. The Dyers’ Company gave us a unique opportunity: a live commission with a rich historical context and a meaningful purpose. It wasn’t just about exploring emblematic design; it was about connecting with the traditions of a centuries-old Livery Company and contributing to its living legacy. The brief was collaborative in nature with direct client interaction, which is perfect for building confidence and giving students a real taste of what client-led work is like.

Real-World Experience: How Live Briefs Prepare Students for the Jewellery Industry

Lili: Projects like this are really transformative for students. Creatively, they’re challenged to take a real brief and turn it into something visually and symbolically compelling, which really pushes their research and design thinking. Professionally, they get a taste of what it’s like to respond to client feedback, present their ideas clearly, and work within real production constraints.

It’s very much like the collaborative, iterative process you’d experience in the design industry, and it helps them build key skills - communication, resilience, adaptability. By the end of it, they don’t just have a piece to put in their portfolio - they’ve actually lived through the whole journey of a professional commission.

Jasmin: The project replicates the way studios actually work. Students have to learn how to understand a client’s needs - what they like, what the piece means, what their budget is - and how to ask the right questions when clients can’t quite articulate their vision. They then need to turn those abstract ideas into designs and manage expectations about what’s possible. It’s also about iteration: generating concepts, presenting them, listening to feedback, and refining the design, sometimes when challenges come up, like cost or materials.

They also get exposure to sourcing and materials - thinking about metals, stones, costs, even ethical concerns, all of which are now so important. And, of course, they start to understand technical constraints: which processes are feasible, how to prototype, and how to ensure quality. That’s why I say a live brief like this bridges the gap between academic learning and the profession. It gives students a taste of the complexity, collaboration, and problem-solving that defines life as a jewellery designer.

Steve: Students approach projects differently when they know there’s an actual client involved, and gain so much from seeing a finished product used in a real-world context. Often, when we’re teaching, it’s not artificial, but it is practice - it’s hypothetical. This project, however, had a tangible concept and a real purpose, which made it far more meaningful.

Students are exposed to the realities of working in jewellery: deadlines, technical constraints, client expectations, and problem-solving. It’s not just about making something beautiful; it must work, be feasible, and satisfy a client.

Amy: Working with The Dyers’ Company was such a privilege. It was a live commission, unlike anything else we’d done on the Foundation Programme. For me personally, it was a real challenge to work closely to a brief developed by the company and our course leaders - designing something that had a specific purpose and concept, just like you would in the industry for bespoke pieces.

From Blank Page to Bold Ideas: Supporting Student Confidence, Creativity and Skill

Jasmin: During live projects like this one, I guide students on the technical aspects, wearability, and production feasibility of the piece, while giving them freedom to develop their ideas. I explain the importance of fully understanding a design brief, researching, and creating mood boards. Even with a clear client brief, I encourage students to infuse their designs with their own personality and draw inspiration from subtle details in the world around them - like a leaf floating or the intricate components of an object.

Many students can feel daunted by creative block or the ‘empty white page’, so I guide them through fun and playful exercises to prepare them for diving into the design process. It's incredibly rewarding when their ideas click and they get excited. My role then shifts to helping them channel that energy, transforming their concepts into a cohesive, brief-fitting project.

I also try to show the students that there are no bad ideas – if a design isn’t satisfactory yet, it just means the development process isn’t finished or the direction needs slight adjustment. One the most rewarding experiences is seeing students who doubted their design skills, become astonished by their own creativity.

Steve: When I joined, the process had already begun. Jasmin and Lili’s input had been instrumental. The students didn’t really have the technical know-how or time to produce the piece. My role was to talk them through the process I used to produce the design The Dyers’ Company had chosen. The clients wanted to meet the manufacturer, so I went to Dyer’s Hall and explained how to enhance the design a little by adding colour through the addition of a precious stone – something designers often do in the industry.

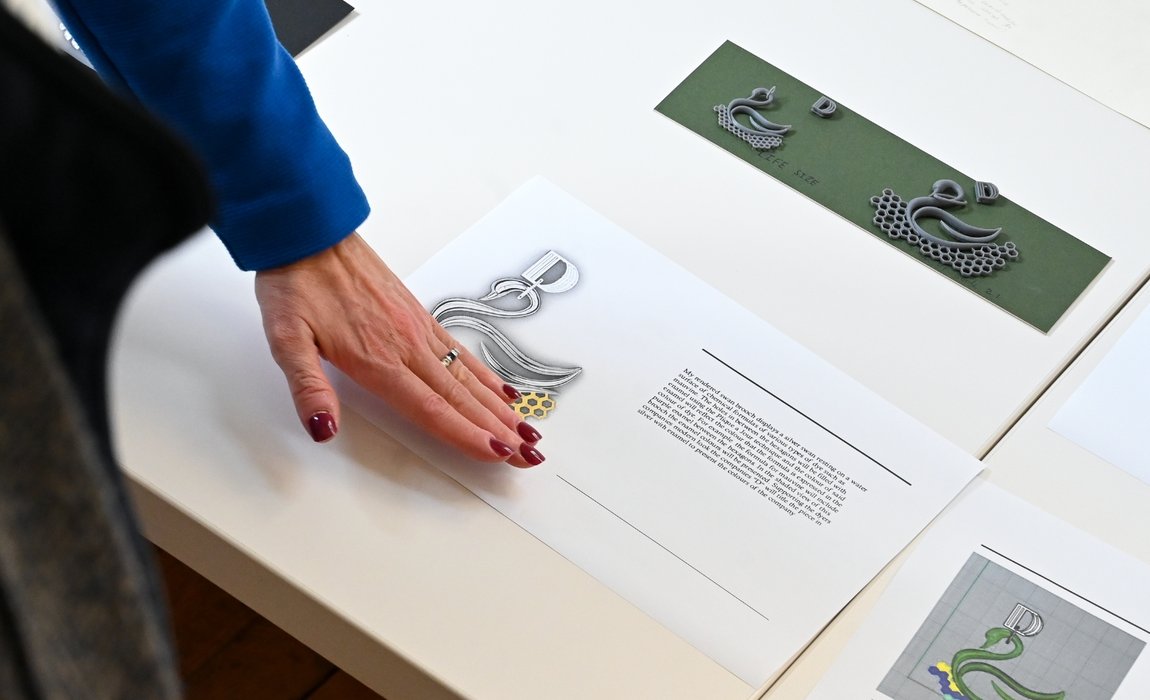

The students had created a 3D model that was easy for the client to access. Understanding how a concept translates into a wax mock-up was probably the most useful part of the process for them. I made a few tweaks to make the design producible in multiples. The Dyers’ Company liked the idea of using it as an annual award, which brought up technical considerations for repeated production.

I brought that process back into the classroom so the whole class could see how a design becomes a practical piece. If we’d had more time, they could have done the technical work themselves, but giving them input as we went along helped them experience the client relationship, how perspectives change during the process, and see how ideas are transformed into reality – insights they’ll use going forward.

Laurie: I was new to CAD, so being able to talk to different tutors at the Goldsmiths’ Centre was really helpful. I worked with Jasmin, who specialises in CAD, and Steve, who does a bit of CAD but mainly works by hand. Getting feedback from them, not just the client, but also my peers, was really valuable. Communication was key - not just with the client, but with everyone, including my classmates. I showed them a few designs, and Amy did the same, so we could discuss what we liked and didn’t like. It was like a think tank, which was a great way to develop my ideas. We weren’t keeping our ideas to ourselves, and it was nice to take inspiration from other people’s work.

When it was all finished, Steve was great about showing me the different stages of the process. We got to see it first coming out of the 3D printer in resin form, then Steve showed me the tweaks he had made and the suggestions from The Dyers’ Company. Finally, we saw it cast and completely finished. It was amazing to see everything that goes into bringing a design to life. I created the design, and it was really nice to be kept in the loop the whole way.

Jamie: This project reminds us that while experience and technical skills are important, creativity and fresh ideas - supported by teaching staff - play a huge role. Without Lili, Jasmin and Steve, this clearly wouldn’t have resulted in a viable product.

Understanding Clients and Navigating Real-World Constraints

Laurie: It gave me a much deeper appreciation of what goes into doing a design, especially managing client expectations versus my own. I also had to deal with disappointment when something I've worked on – an aspect I liked – wasn’t what the client preferred. At the end of the day, they’re the client, so I had to adapt to what they wanted without losing the core concept of the design. For example, the brooch was originally supposed to work both as a brooch and hang on a chain, but that idea was eventually scrapped. That experience taught me how to manage expectations.

Another big part was working with a client who doesn’t necessarily understand the jewellery-making process as well as my tutors do or even myself. You have to manage their expectations too. I remember talking to Steve about it, and he explained that a lot of the time he’ll get commissions where certain ideas just aren’t possible - especially if there’s a strict budget. Sometimes you just have to be upfront with the client and say, “Sorry, but that can’t be done.” That really opened my eyes, because it showed me that sometimes you just have to accept that something isn’t possible, no matter how good the idea seems.

Amy: After the design stage, we were able to pitch two ideas to the company and receive feedback on the initial designs. Their feedback was incredibly valuable and helped me to build on one design further, changing certain elements and aspects of the composition. It was the first time I had the opportunity to work with clients in this way, and it was fascinating to learn about the iterative design process involved when working with clients.

The most important industry relevant skill I developed over the course of the project was client communication, how to effectively communicate a design concept through both words, hand rendered drawings, CAD renderings and 3D CAD models in order to allow the clients to fully understand the idea and concept. Taking on that feedback allowed me to keep improving the design, rather than becoming fixated on a single idea.

Jasmin: It’s an opportunity for them to really understand client needs. They learn to interpret a client’s preferences and budgets. This often requires active listening, thoughtful questioning, which often involves “reading between the lines”, - all crucial communication and empathy skills in the industry. The briefs also teach problem-solving within constraints. Whether it’s working with specific materials or even aesthetics, staying within budget, or meeting a tight deadline, students must learn to be creative and innovate while navigating boundaries – a common challenge every professional designer faces.

Modern, Versatile, and Meaningful: The Making of the Dyers’ Swan

Jamie: The final piece really brings the Dyers’ swan to life in a modern and beautiful way. It moves the Dyers’ forward while also using a jewel to show mauve - the colour of the first modern dyestuff. Each consort will receive the swan to wear throughout the year. It’s likely to be the ‘badge’ for most occasions, except the most formal ones, clearly identifying the wearer as the Prime Warden’s consort.

For women, it works as a brooch that goes with almost any outfit - simple and elegant. For men, it can be worn on a lapel, looking stunning and perfectly appropriate on the silk of a black-tie jacket. Its versatility, unisex appeal, and contemporary style all help present the Dyers’ as forward-looking and, well, classy.

Laurie: It’s such a privilege to be involved with a company with so much history and see the final piece come together from the initial brooch design, knowing that I’m now a small part of that story. The aspect The Dyers’ Company really liked about my design was that it had a traditional yet contemporary look. We did two designs, and the first one, which was selected, was simple and flowing. The second one had a lot more colour and was more complex. In the end, I took a bit of inspiration from that second design and added it into the first, so all the ideas kind of came together. They’re likely making a whole range of them, which is really exciting.

Steve: The great thing about this project is that it started as a real-world idea with clients involved. They could have said, ‘We don’t like any of these designs,’ and that would have been fine, but it became more than that. It’s very collaborative - students, tutors, Lili facilitating communication, and another company. The Goldsmiths’ Centre’s connection with other organisations broadens networks. Seeing a finished piece that the client wants and is prepared to pay for is hugely valuable for students. At the end of the day, you don’t just make pieces to put in a drawer - you have to make them work commercially.